This article first appeared in my LinkedIn newsletter: The Sustainable Business. Join the conversation there!

If you work in corporate sustainability or follow greenhouse gas (GHG) reporting news, then you’ve probably heard of Scope 4 emissions. The topic has come up several times in my conversations with companies and organizations about sustainability reporting.

Scope 4 has certainly piqued my interest since Rheaply’s embodied carbon reporting is based on the theory of displacement and avoided emissions. You might think Rheaply is thrilled to learn about the rise of Scope 4 emissions, but it’s more complex than that. Before we dive into my views, let’s talk about what Scope 4 emissions are and why people care.

What are Scope 4 emissions?

Scope 4 emissions is an unofficial term that companies and professionals use in an attempt to categorize and quantify avoided emissions. The term Scope 4 is new but the concept of avoided emissions is not. According to a World Resources Institute article from 2013, avoided emissions are reduction efforts that occur outside of a product’s life cycle or value chain.

For example, tire manufacturers can enable their customers to save fuel by producing fuel-efficient tires that reduce rolling resistance. Therefore, the customer is able to avoid emissions by using a superior product. This perspective extends beyond the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s accounting framework, which primarily focuses on the reporting company’s direct and indirect emissions.

Let’s pause for a quick recap on scopes 1, 2, and 3.

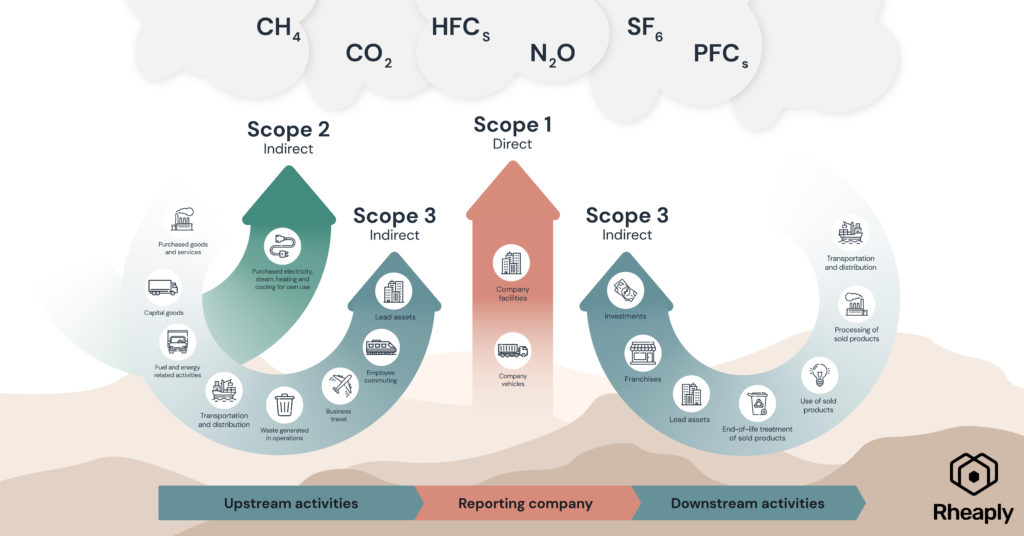

- Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from company-owned and controlled resources.

- Scope 2 emissions are owned, indirect emissions from the generation of energy from a utility provider.

- Scope 3 emissions are everything else. In other words, the most widespread indirect emissions which are not directly owned by your organization.

For the most part, you can think of the first three scopes as emissions that are being released into the atmosphere as a result of the actions of the reporting company and their value chain. Whereas, Scope 4 emissions account for the greenhouse gasses that never make it into the atmosphere because an alternative product was selected. And not just any product, but an alternative that has less life cycle emissions than the original product.

It’s important to remember that avoided emissions are separate from scope 1, 2, and 3 so you can’t use them to offset or adjust emissions in an organization’s greenhouse gas inventory.

Why are people talking about Scope 4 emissions?

Scope 4 emissions have become the talk of the town because organizations like to get credit for the good work they do. Right now, there’s no credible, best practice for reporting avoided emissions.

Despite the lack of a global reporting framework, organizations are still moving forward with calculating avoided emissions. Keep in mind, these methodologies can vary greatly and are difficult to compare and verify.

Scope 4 emissions represent an increasingly important gap in carbon emission disclosure and reporting. Interpreting these avoided emissions can help organizations better understand how they can drive important climate action. With a firm understanding of Scope 4, organizations can clearly outline the potential outcomes of developing a more sustainable product or service, improving transparency for stakeholders.

Reuse and Scope 4 emissions

I typically think about the carbon impacts of reuse in three ways:

- The reduced volume of goods purchased by an organization and their associated emissions.

- The reduced emissions associated with the disposal and treatment of waste. The less waste you produce, the less emissions from processing it.

- The reduction in emissions through providing reused material alternatives. This is particularly important for high-impact and high-waste industries, such as construction.

Of those three, the last aligns the most with Scope 4 emissions. Let’s consider construction materials as an example. If an organization chooses to source used construction materials for a new build, then they are avoiding the life cycle emissions associated with the typical, new material. This example makes it sound like we are giving all the credit to the organization that selected the used material and included it in their project. But what about the organization that supplies the used materials – otherwise known as the previous owner – do they get any credit? A lack of standardization and best practices makes it challenging to properly account for avoidance credit.

If you ask me, focusing on how to report avoided emissions shouldn’t stop your organization from making decisions that put the environment first. And let’s be honest, a lot of companies are still struggling to account for all 15 categories that fall under Scope 3 emissions. We see a lot of alignment between reuse and several categories under Scope 3, such as Categories 1, 2, 5, and 12.

I’m not saying all this chatter about Scope 4 is irrelevant but put it into perspective first. Don’t let this hot topic take away your focus from tracking and reducing your organization’s scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions. More specifically from a reuse standpoint, don’t slow down your efforts to scale reuse programs because there’s no standardized framework for reporting these efforts. There’s no time to waste, and I invite you to share some of the reporting challenges you’re facing in the comments below.You know I always welcome discussions on how reuse can make an impact on sustainability goals and net zero plans.