Thanks to the work of countless climate activists, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been widely embraced as a metric to measure, and improve, our progress towards a more sustainable world. These emissions — sometimes referred to as carbon emissions, as the majority of GHG emissions are carbon — trap heat in the atmosphere and thereby contribute to climate change. In that sense, it’s pretty straightforward for sustainably-minded companies: the lower your emissions, the more sustainable your operations.

Unfortunately, it’s more complex than most understand, and that is because of the challenge of defining what exactly makes up your emissions.

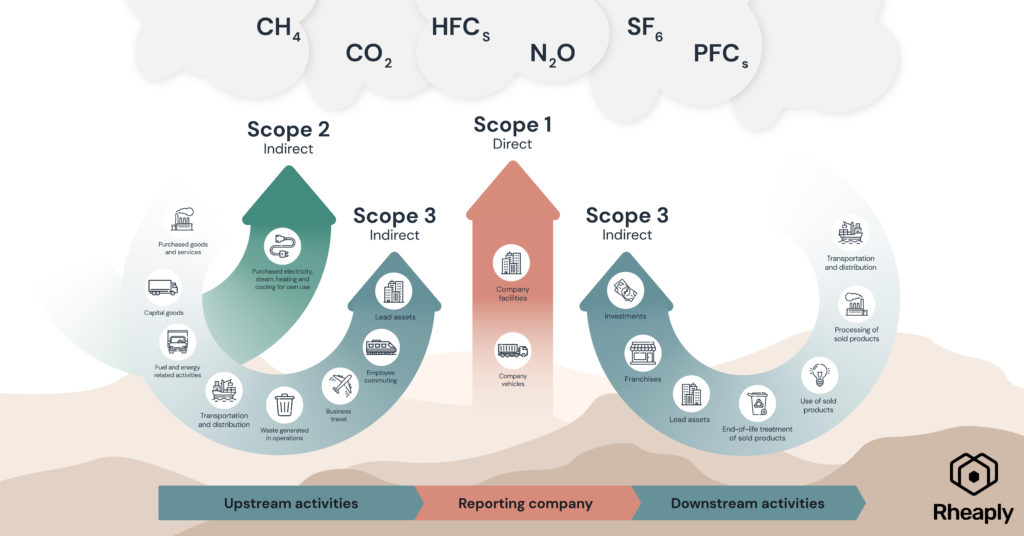

Company emissions can be broken down into different categories, referred to in the industry as “scopes.” Scope 1 emissions are the most straightforward: these are emissions that you directly produce as a company from a source that you own. For example, if you have a generator or furnace on-site, that would count as Scope 1. So too would flying a corporate jet or driving a company vehicle.

Scope 2 emissions, per the EPA’s definition, are “indirect GHG emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat, or cooling.” You may not own the equipment that generated the electricity your company purchases from a utility company, but you do clearly cause those emissions through your business activities.

Both Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions are relatively easy to tie back to the company in question, and therefore have become common when it comes to measurement. When companies say they are aiming to reduce their carbon emissions by 2025 — or even achieve “net-zero emissions” — they are usually referring to Scope 1 and Scope 2.

The issue, as you can probably guess, is that there is another scope, and it’s one that is underrepresented in emission calculations today. In a basic sense, Scope 3 is “everything else” up and down the supply chain that goes into operating your business. For example, let’s say you buy a ream of paper from the store. You likely didn’t drive a truck into the forest to cut down the trees and transport them to the mill — because your business requires paper, however, those emissions were still necessary, even if they occurred via a completely different company.

Given the scale of supply chains, it is perhaps not surprising that the vast majority of companies’ emissions (65-95%, according to Carbon Trust research) are Scope 3. It is also unsurprising that Scope 3 emissions are accounted for far less than Scopes 1 and 2. Many people are completely unaware of Scope 3 emissions, or don’t think they can (or need to) do anything about them since the emissions are only indirectly caused by their company. To that end, it should be noted that there is no SEC requirement for Scope 3 emission disclosure. (Yet, there is a climate proposal). But even if a company does want to account for their Scope 3 emissions, they are inherently far more difficult to measure than emissions from the first two scopes.

For these reasons, Scope 3 disclosure numbers are often dispiriting. For example, according to a new report from the nonprofit Ceres, out of the 50 largest food companies in North America, only three (Hershey, Starbucks and Mondelez International) both disclose their Scope 3 emissions and include Scope 3 emissions in their science-based targets. This is despite roughly 80-90% of emissions for food industry companies occurring in this scope.

But here’s the problem: you can’t have a serious carbon reduction goal (or discussion) without some way of measuring Scope 3 emissions. Because such a large portion of company emissions tend to be Scope 3, even the complete elimination of Scope 1 and 2 emissions — as laudable as that would be! — would represent just a small victory in the war against rising GHG emissions and climate change.

Luckily, we know that measuring and targeting Scope 3 emissions is possible, because some forward-thinking, sustainability-focused organizations are already doing it. Enterprise, local government, and higher-ed professionals are in hot pursuit of CO? data calculated from the embodied carbon of resources in order to hold themselves accountable to meet carbon reduction targets and monitor and report their GHG emissions data. Scope 3 emissions are also “particularly fertile ground for opportunities to identify synergies and collaborate,” since Scope 3 emissions from any given company necessarily overlap with other companies’ emissions as well. For instance, GM — a company whose emissions are estimated to be 97% Scope 3 — has not only “set strict emission reduction standards for companies along its supply chain,” but is also empowering suppliers to make their operations more sustainable by helping them locate renewable energy sources.

It’s also important to note that supply chain emissions can be reduced in numerous ways. While renewable energy is often the first thing that comes to mind, we must remember that the product lifecycle (which I touched on a bit in my previous newsletter edition) provides an enormous opportunity for emission reduction as well. By focusing on reuse and extending the lifecycle of products and materials, we reduce the need for new products and materials, and the emissions that accompany their production.

The Scope 3 challenge is a big one, but getting companies to buy in and collaborate will go a long way toward tackling it. If you’d like more insight on how to put together a plan for reducing your Scope 3 emissions, I’d be happy to connect and share some guidance. Or if you have any experiences of your own with measuring and targeting Scope 3 emissions, I’d love to hear from you in the comments.